Reading the Syllabus

If you are a professor or a grader, you're probably reading this and saying, "Yes!!! I hope all my students read this."

If you are a student, you are probably thinking: (A) "this really doesn't matter," (B) "no one would ever do this," or (C) "is he talking about me?"

If you are in group A, you should be in group C. If you are in group B, you are totally wrong. If you are in group C, then you should rightly be embarrassed. Fortunately, there is hope for you if you recognize your faults and turn away from them.

Professors are required to create syllabi. (Or is it syllabuses?) They are designed to record what the class did so we can look back at it and also to tell the students what they should be doing over the semester.

The main content of a syllabus is the information students need to know to get through a class. It is the way higher education has developed to pierce the veil of mystery and provide help to the students who have elected to pursue further study.

Sort of like a Facebook post or a mass e-mail, a syllabus is a way to tell everyone the same thing at the same time in the same way.

To rehash that last point: syllabuses tell EVERYONE the information they need to get through the course AT THE SAME TIME.

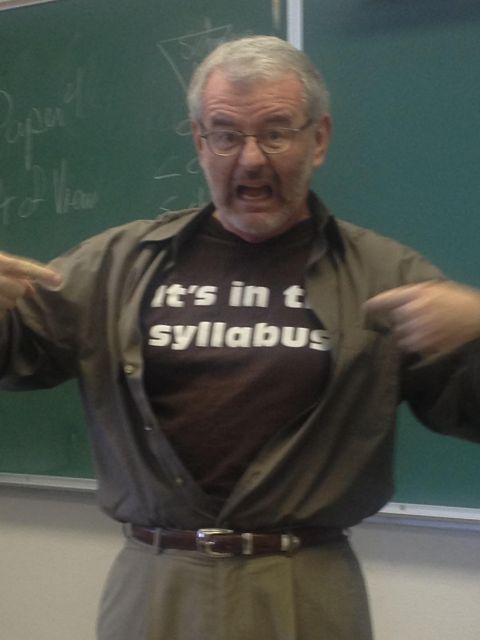

The whole point of a syllabus is to avoid answering everyone's questions individually, whether in person or via e-mail.

An Illustration of the Problem

Imagine carefully drafting an e-mail to invite 40 of your closest friends to a party. This is like a syllabus.

Now imagine 25 of those individuals calling to ask you questions that were clearly explained in the e-mail. "What time does it start?" "What should we wear?" "Can I get directions to your house?"

Assuming the necessary information was actually in the e-mail when it was sent, by about the fifth phone call you would be ready to spear someone through the heart.

Next imagine you held three parties every six month, and repeated this year in and year out for two decades. There is a level of quiet frustration that would builds over years of the repeated, minor aggravations.

To be fair, there is the possibility the professor something left something out. For instance, in your invitation writing, the first year you might not include your address. Woops! But every year after that you would include your address and maybe a link to the Google Map for it. Likely the error would not exist for long if you repeated the process several times.

And yet if your friends are anything like students as a whole, you would continue to have friends calling you for information that is clearly explained in the invitation.

You would stop holding parties after a few years. Or, you might stop answering e-mails requesting answers to the obvious.

For professors, they continually get new students who continue to not read the syllabus. They have to keep teaching so they can eat. Unfortunately, they are trapped in a cycle of ignorance not of their own choosing.

It's not just the Facts, Ma'am.

Sometimes student questions are not explicitly in the syllabus, but that's often because they don't belong there. Not because the information wouldn't be somehow useful, but because the information is (a) easily obtainable or (b) self-evident.

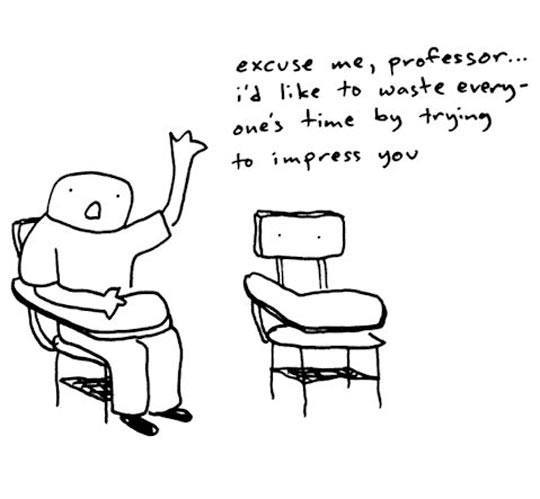

For example, on the first day of a graduate philosophy class, one of my fellow students raised his hand and asked, "Where do I get the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy?" (This was spoken in Hillbonics, but I have translated it here for you and taken out the intense bib overall accent.)

You see, the professor had referenced some peer reviewed articles in the syllabus that we would read in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. He did not give the website because, well, it seems self-evident that the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy is on the internet. Google is a free service, my friends. Foolishness like this has happened more than once.

Despite these warnings, some questions are good questions. For example: "Having consulted my syllabus, I would like to compliment you on your thoroughness." (For some discussion on student questions, see my earlier post here.)

In reality, there are some questions that need to be asked. If you need to ask, do so. But first have the common courtesy to check out the syllabus to save the professor some aggravation. Besides, it makes you look smarter.

Final Thoughts

I have rarely meet anyone who teaches in Higher Ed who did not get into the business because they enjoyed helping people learn. Even the nerdy, super-introverted Engineering professors I had honestly cared about students. (See what I did there?)

However, make it easy on your professors by being a good student. Good students read the syllabus, are considerate of others, and are diligent with their opportunities. This doesn't mean you will get an 'A', but may mean you are remembered positively.

It also may make your professor's day.