Raising Faithful Kids in a Skeptical World

It’s a lot easier to raise a skeptic than a child with a mature faith.

This is not a statement about behavior, but about true fidelity. That is, faithfulness that includes both a profession of faith and a solid foundation for that faith.

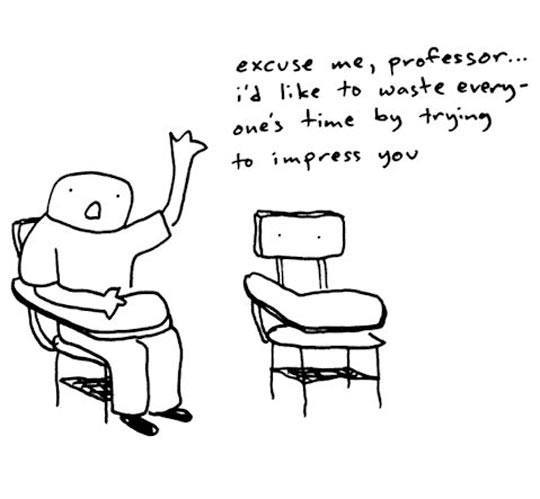

It is much easier to teach a child to poke holes in the ideas of others than to hold fast to cogent, explanatory truths.

As a result, there is a constant temptation to build buttresses of truth around our kids without exposing them to challenges to the faith. This is good when they are young, because it prevents confusion. It is a dangerous thing over time because it builds a false sense of confidence.

The Place for Honest Doubt

Comprehensive, absolute certainty is a dangerous thing. There is little doubt about that.

Being entirely certain about every detail of one’s own understanding of Scripture, the veracity of the traditions of one’s youth, and the methodology appropriate to determining truth can lead to pain and difficulty over time. Much of that is unnecessary.

There is a fundamental difference between holding a position with absolute certainty and holding it in faithful confidence.

This is because being faithful does not require abandoning the intellectual task of asking questions and considering alternatives. Issues such as the proper mode of baptism, the right style of worship, the way the salvation is explained are all points where legitimate questioning is warranted. After all, a lot of faithful people in the history of the Church have stood on each side of those questions.

But there is a place for asking even more significant and sensitive questions. Is there a God? Certainly, a fool says in his heart there is no God (Ps 14:1). However, this doesn’t mean that kids shouldn’t ask the big questions and honestly pursue truthful answers. Helping kids ask those in a space where they have the emotional and spiritual resources to struggle through the mire of doubt is important.

It’s also much easier to teach fideistic adherence to dogma than to teach kids to think through doctrine rightly.

In the end, fideism presents an anemic form of Christianity that skeptics can punch holes through with ease. Then, when faced with intelligent, cogent challenges to their faith, an untried faith system will fall apart.

Always Another Question

As I said, it is easier to raise a skeptic than a faithful child.

Much of contemporary culture trains children to expect a higher degree of certainty and a greater volume of proof for questions of religious significance than anything else. For example, people choose their presidential candidates without knowing everything about them and whether everything in the candidate’s worldview meshes. People take jobs without knowing in gross detail every possible work responsibility, the date of future promotions, and whether the company’s corporate office in Paris might have spent too much on cognac last year. Folks use electricity without understanding where exactly it came from or how it was generated.

In contrast, some critics of religion seem to expect an unassailable record in all of history from the religion itself and also each adherent of the religion. They demand that every possible question be asked and meshed with every other solution offered for all of time. Variety in such responses over history—even to secondary and tertiary questions—is considered evidence that the central truths cannot be true.

Many of these questions are fair to ask and Christians should be prepared to discuss them, even if in general terms. Christians need to be prepared to admit that the history of every religion is tarnished by error and insincerity. Christians need to be willing to communicate that there are some doctrines about which reasonable people can debate.

The reality is that every religion, even Christianity, has open questions about some aspects of it. This is a function of the human conduits of the religion and our finiteness. Every religion has a checkered history with abuses. This is because religions have humans involved and humans tend to be self-centered and imperfect.

This means that for someone looking for objections, there are always additional questions to be asked. If the standard of acceptance for religion is that every question is answered, that standard can never be met. There is always one more question to be asked.

The world is training children to be skeptical, if not agnostic. The Church—especially the parents of children—need to be prepared to help develop a curious, cautious, but not incredulous demeanor in their children.

We need to teach our children to seek the best answer, not the perfect one. We need to demonstrate the power of the gospel to transform and redeem. Once a child understands the reason for the hope within us, they will be better able to ask questions without losing their faith.

We need to teach and demonstrate to our children that the Christian faith has integrity and is founded on the absolute objectivity of God not the absolute certainty of our positions. We can have a high degree of certainty about what we believe without dismissing questions. We can demonstrate confidence in our faith by chasing down answers to difficult questions and admitting when we have more investigation to do.

Retooling Parenting

In some day gone by it may have been possible for kids to pick up enough of a basis for their faith by osmosis. Probably not, though, since the failure to present a credible, cogent faith for generations helps to explain the radical rejection of the trappings of a Christian ethic.

The present culture is one that will not accept Christianity without a great deal of explaining. It also will not allow Christians to live consistently with a robust Christian faith without challenging every inch. We do disservice to our children if we do not equip them and assist them to wrestle with the core doctrines of the Christian faith.

Parenting will look different in our present age than it has in the past if we are to give our children what they need to live as faithful pilgrims in the world. That isn’t to say that it will look different than what it always should have been. In fact, the external pressure on the Church may be a benefit to our sanctification as it forces us to return to our proper responsibilities.

There’s no reason to doubt that Jesus was nailed to the cross. Ultimately, I trust what Scripture says about Jesus’s crucifixion because I also trust what it says about his resurrection. And that’s what we should be celebrating this week.