The Snakebite Letters - A Review

If there is anyone who I think might possibly pull off a version of C. S. Lewis’s Screwtape Letters, it would have to be Peter Kreeft.

Kreeft is deeply steeped in Lewis and in the same source material that Lewis was infatuated by. Kreeft writes well, is witty, has similarly strong opinions, and generally expresses them clearly.

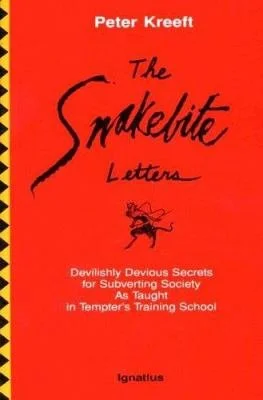

In The Snakebite Letters: Devilishly Devious Secrets for Subverting Society as Taught at the Tempter’s Training School, Kreeft takes a swing and misses the mark.

The book is entertaining and at points helpful. Kreeft is at his best when he is engaging modernity with a pre-modern, Christian vision. That is exactly what he does through much of the book.

Kreeft identifies the real, spiritual nature of the ongoing strife in the lives of Christians. He notes how the media helps saturate every minute with unhelpful thoughts, especially about sex. This leads to undermining any helpful conception of chastity and advocacy for abortion, often as a matter of convenience, even by those who recognize that it is reprehensible and evil.

Somewhere Kreeft here slips away from talking about Christianity to talking about a defense of Tridentine Roman Catholicism, which is the particular sect of Christianity that he converted to as an adult. Much of the rest of the book shifts away from spiritually helpful resistance to modernity to his particular concerns about the internecine struggles within his own tribe. More than many of his other books where he dabbles in pro-Roman apologetics and swipes against the Reformed faith, this book majors in those topics.

Kreeft, of course, has every right to defend his particular version of Christianity. This is likely a very helpful book for those seeking to evade the weird balkanizations within the membrane of Catholicism, with Trads that hate the pope but are stuck with him and Liberals that often dislike the historic teachings of Roman Catholicism that serve as the supreme authority but like the pomp and circumstance. As odd as so much of Protestantism is (and it is odd!) the tensions within Roman Catholicism are sometimes baffling.

Lewis’s appeal in Screwtape is that he is arguing for mere Christianity. That is, his book is generally applicable to a wide range of Christians. Kreeft leaves most Protestants behind for much of this book.

More significantly, however, Kreeft is simply not as capable as carrying out the schtick as Lewis. I’m a fan of both Lewis and Kreeft and have found Kreeft to be one of the most enjoyable contemporary writers of apologetics and wit. His inability to consistently carry the motif is more a testament to Lewis’s brilliance than any detriment to Kreeft. There are times where Kreeft’s own didactic voice comes through and it is clear that it is him talking to the reader, not the demon Snakebite writing to his apprentice, Braintwister. There are holes in the plot, the wall isn’t quite sound, and it becomes possible to catch a glimpse of the man behind the curtain.

The fact that Kreeft can’t pull off a copycat of Screwtape is probably a sign that so many others that try it shouldn’t. As Kreeft notes in his introduction, Lewis would likely have “wanted such ‘plagiarisms’”. It’s not the copycatting that is the problem, it is that the bar is so high that everything else seems like weak sauce—even what Kreeft provides here.

My appreciation for Kreeft remain undaunted. I was left a little unimpressed by The Snakebite Letters, but not really disappointed. It’s a credit that Kreeft came as close as he did. Who knows, the next person to try may actually pull it off. I doubt it, though.

There’s no reason to doubt that Jesus was nailed to the cross. Ultimately, I trust what Scripture says about Jesus’s crucifixion because I also trust what it says about his resurrection. And that’s what we should be celebrating this week.