How Do Views of the Environment Develop?

I've spent the last few years studying Christian approaches to environmental ethics. In the coming months (not years) I will write my doctoral dissertation examining how theological perspectives control people's view of the environment.

In the hundreds of books, articles, newsletters, and blogs I've read, not to mention the hours of video and audio I've submerged myself in, there are some consistent themes in both religious and Christian approaches.

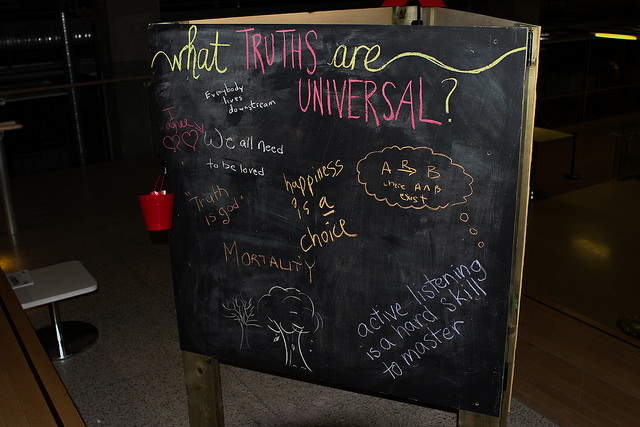

When developing perspectives on the environment everyone has to answer four basic questions:

- What are the sources of authoritative information for my perspective?

- Why does nature/creation have value?

- What role do humans have in caring for nature/creation?

- What is the end goal of nature/creation?

For religious approaches, particularly Christianity, these four questions relate to the doctrines of revelation, creation, anthropology, and eschatology. Non-religious approaches have to answer the same sorts of questions, though they will respond with different vocabulary.

The differing response to these four questions helps to explain how different people with access to the same data can come up with vastly different ethical conclusions. Most of the time we argue about the conclusions, when the deeper issue is how we get to those ethical conclusions.

My understanding of this reality--that these four questions frame environmental ethics--was driven home by my post last week at The Gospel Coalition. The post explained why Christians can and should participate in Earth Day activities.

Some of the comments on the post made it evident that the people so anxious to voice their opinions publicly hadn't bothered to read the post. However, many of their responses demonstrated particular answers to these four questions.

Responding to Four Key Questions

As an evangelical Christian, my governing source of authority is Scripture. This is consistent with sola Scriptura, one of the five central concerns of the Reformers. However, I also take into account relevant scientific data (experience), theological tradition, and reason. These three aspects complete the Wesleyan Quadrilateral. They all help to form my theology, which in the end must be judged by Scripture.

Creation has value because God created it and inasmuch as it is fulfilling its purpose to glorify God. This keeps me from seeing the created order as merely of instrumental value, waiting to be harvested by humans. It also keeps me from ascribing intrinsic value to creation, which would indicate creation has worth apart from God and may stand in the place of God as worthy of worship. This is more dangerous. Instead, creation has a purpose and should be respected and aided in fulfilling that purpose.

Some environmentalists treat humans as if they are an alien species and a scourge on the earth. This is unbiblical. Instead, we ought to see humans are a unique part of creation with responsibility to steward it. Stewardship implies the responsibility to care for and tend as a gardener, but not to use wantonly. Ultimately God owns creation (as he created it) and we will be held accountable for how we use it.

Finally, my reading of eschatology from Scripture sees a renewal of all creation at the end of time. God will do a mighty work to redeem all of Creation from the curse. This encourages a positive view toward working to preserve creation now, though not in an effort for repristination. This position stands in opposition to some Christian eschatologies that anticipate a cataclysmic annihilation and subsequent recreation of earth. It also opposes an evolutionary worldview that anticipates things will go on as they are now for the foreseeable future.

Summing Up

In the end, despite the mixed response to my post (even among those who seemed to read it), I stand behind my promotion of participation in Earth Day celebrations. I have several reason why:

First, it really is important to rightly steward creation for the theological reasons I listed above. We will be held accountable for how we care for the created order, so we ought to do it well.

Second, participating in Earth Day activities is no more a pagan rite than is going to a football game, singing the national anthem, and madly cheering for your team. Some people at the football game are actually participating in worship of their team or their country. That does not mean that every spectator is. Many of the folks at Earth Day events are secularists who would reject Gaia worship as foolishness, just like a Christian.

Third, some object to environmentalism because many environmental initiatives use centralized government planning and impinge on a free market. This is largely because free market advocates have abandoned the environment. The free market only works when people are internally, morally regulated. Big government is more necessary when people lack self control. This means that free market advocates (as I am) are creating a self-fulfilling prophecy by rejecting environmental concern.

Fourth, events like Earth Day are usually filled with people that need the gospel. This should draw a faithful Christian like a light draws a moth. Seriously: People in community who are working together. If that isn't a great place to start a gospel conversation then there is no such thing.

People should act according to their conscience, illuminated by Scripture. However, I think reason should drive Christians toward more participation in common cause activities like Earth Day instead of fewer.